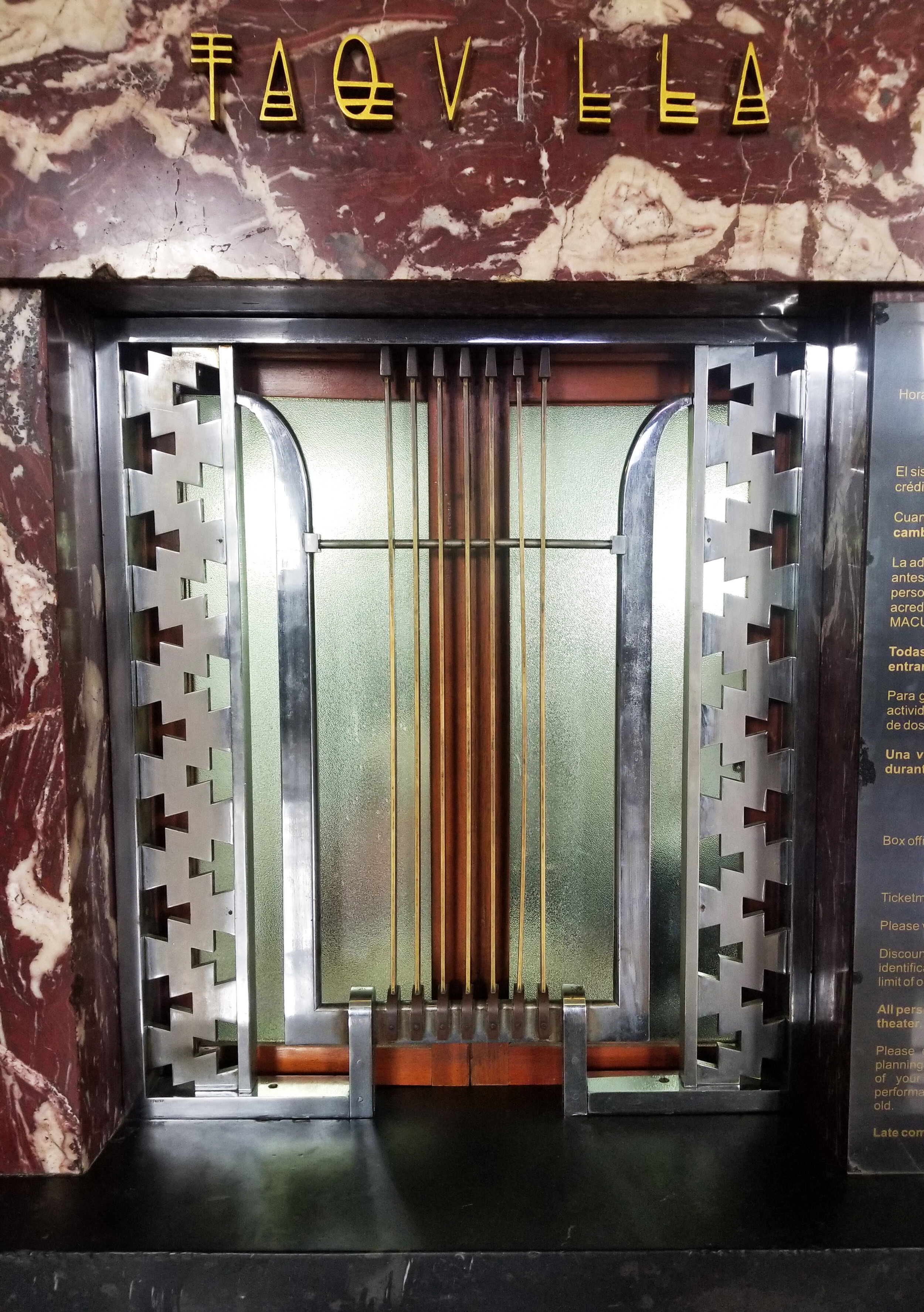

A Reflection - 3.28.21

Eleven years ago on the spring equinox a pattern began to emerge. My rain calendar, 366 individually mounted acrylic tiles, now resided on my apartment wall. On that day, I pulled forward the tile representing the spring equinox and began. Everyday since, as with my life, the calendar changed to mark a new day and record the pattern of my trajectory. A marking that linked my everyday experience to the environment I inhabit. While the aspiration was there that first day, little did I think that a decade later the record would still be playing strong. A daily motion and reflection that ripples forward from that first tile on that first equinox to today.

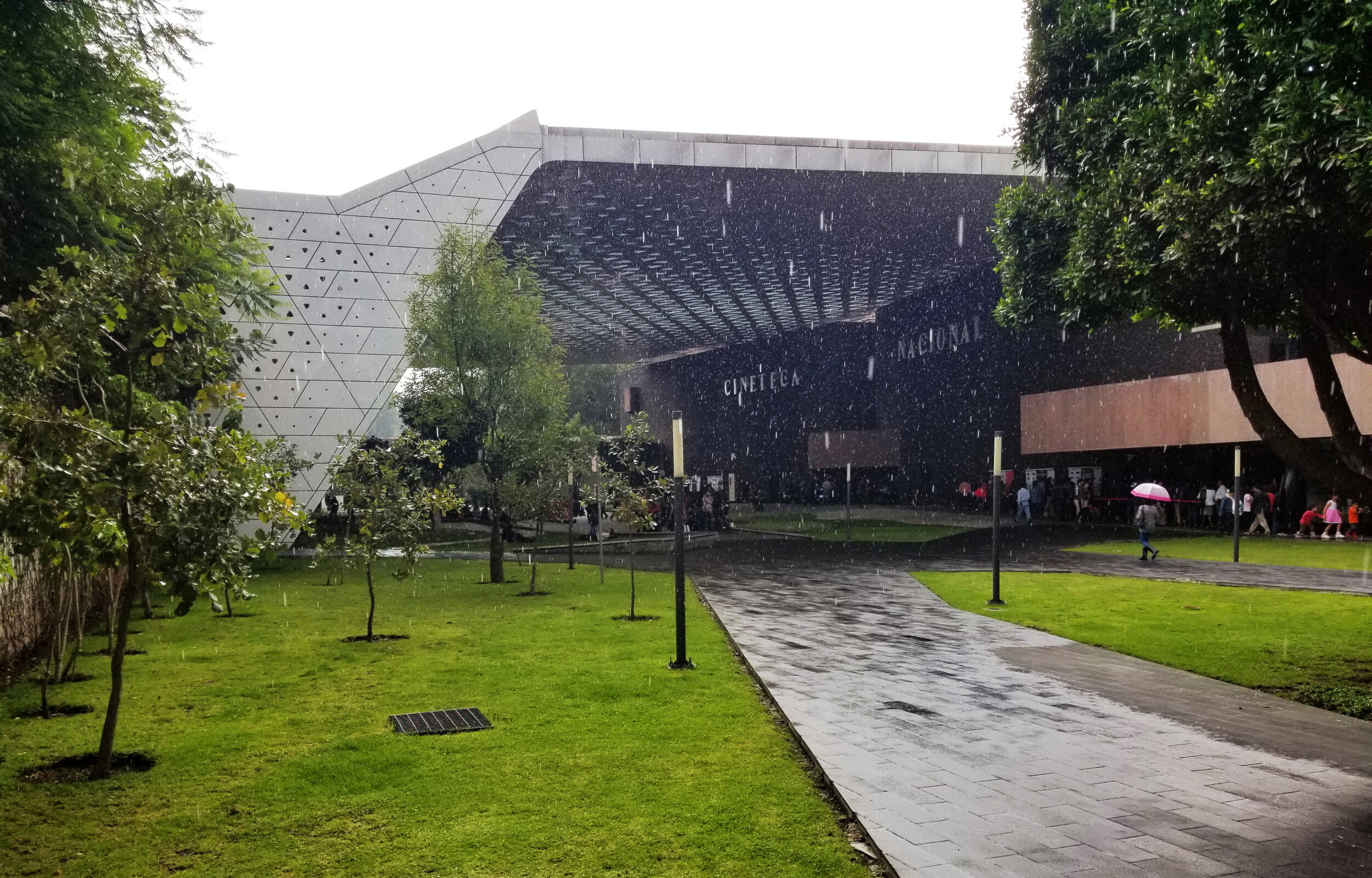

Fittingly, as I write, today is a Rain Day.

Gauge

Inspired by life in the Pacific Northwest, I conceived of my calendar as a way to trace my personal experience of rain. A daily ritual of recording precipitation and my relationship with my place. An enactment and representation of my relationship with rain through art.

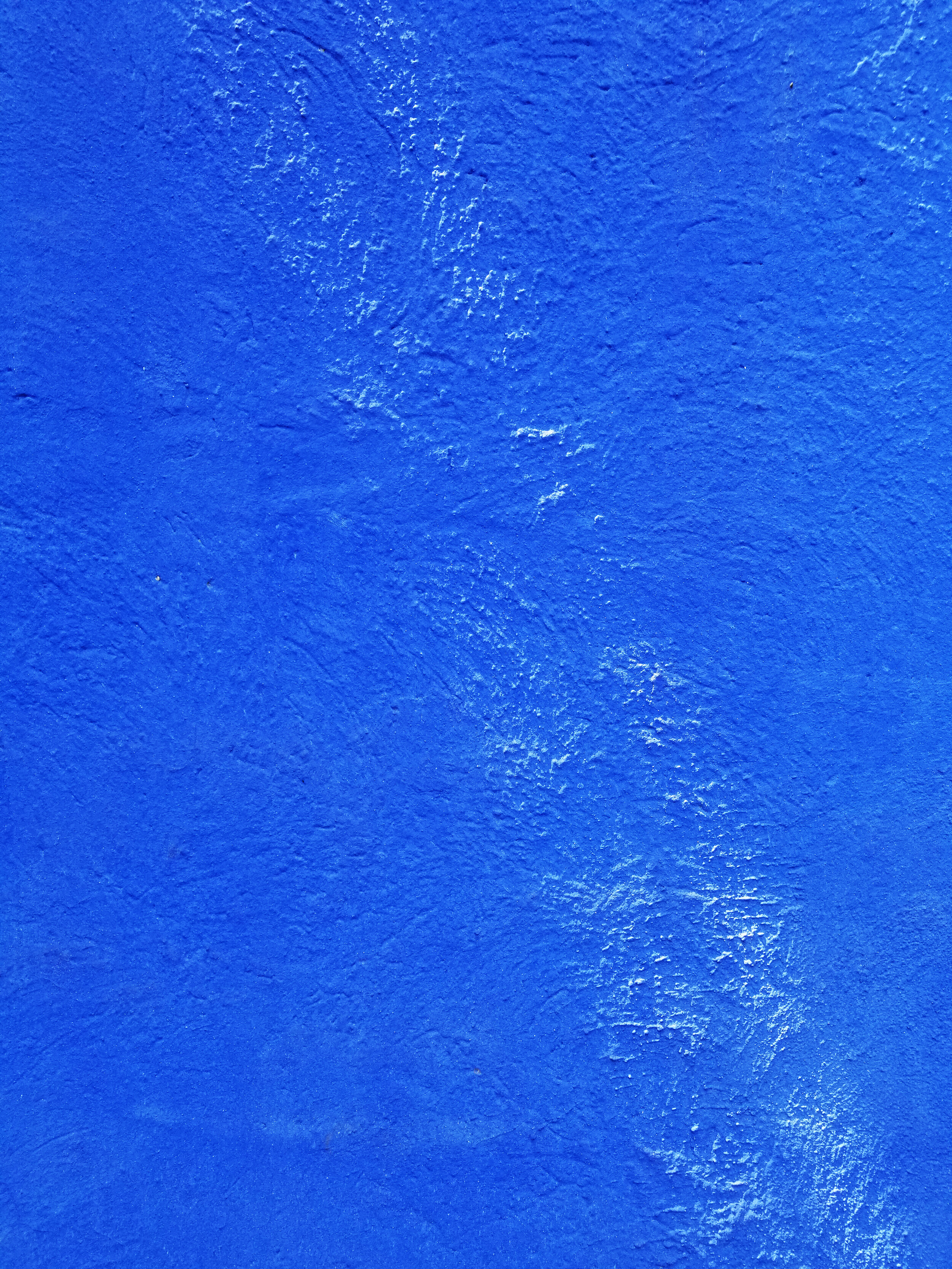

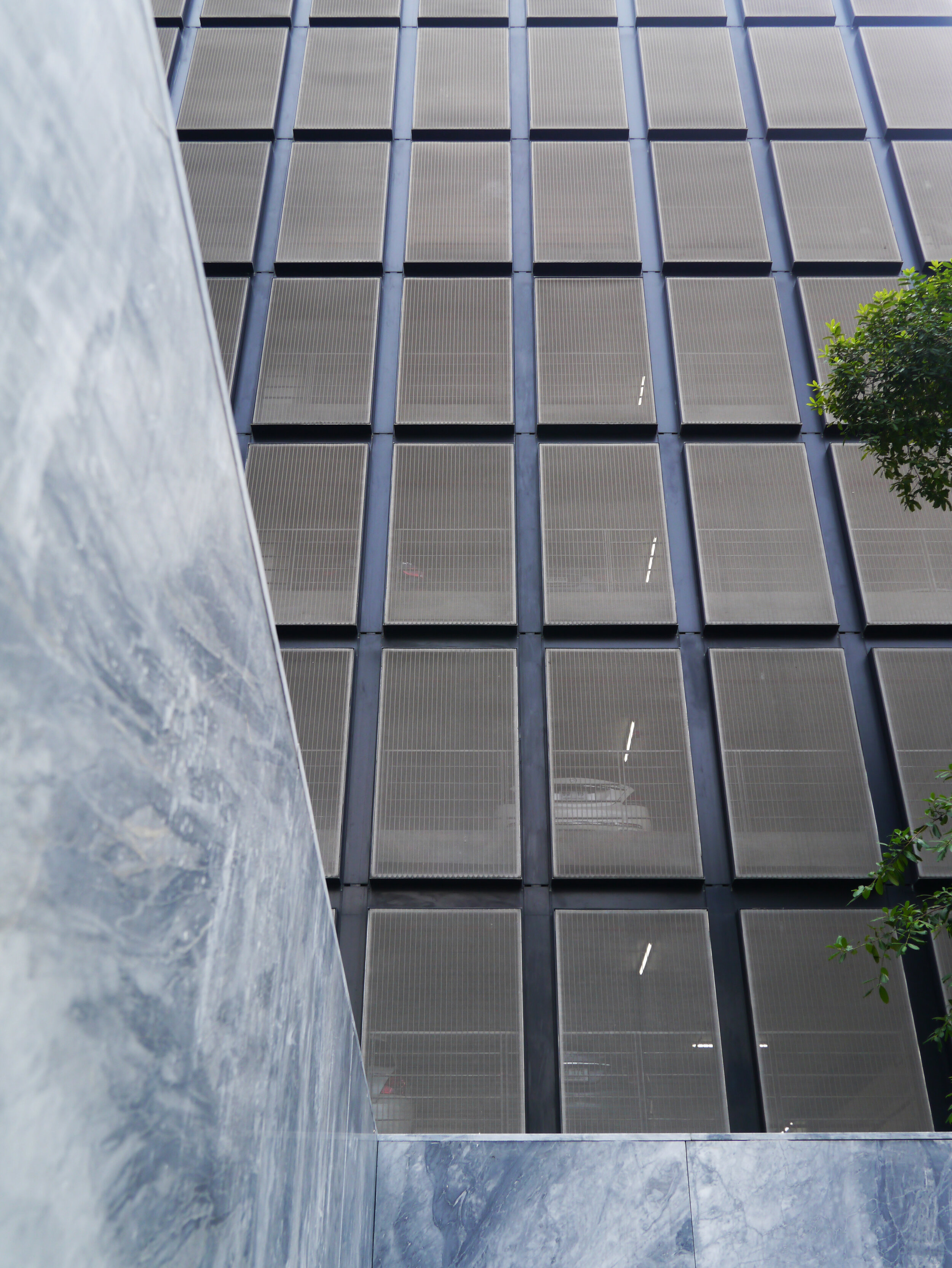

A calendar of 366 individual acrylic tiles. Each morning the forward tile marking the previous day is pushed back to rest flat against the wall and the tile marking the new day is pulled forward to rest on the head of the nail. At the end of each day the current tile is flipped to reflect if it was a 'rain day' (gray) or not (yellow-orange). The gauge is my body. Each tile once pushed back to the wall remains in this state as a record of that day until the year passes bringing me and the calendar back around to a particular tile and day. This ritual and daily observance has become a metronome of sorts. An action that has built layers of knowledge and experience that was barely considered that first day. An action that has come to shape both me (the gauge) and the environment around me.

Small Moments

The calendar design acts to continually question the relationship between individual and the whole. An abstract delineation of space and color set within the continuous flow of time and my life. When I first conceived of the calendar it was a way to come to terms with a life within days and days of rain. I think most residents in Seattle have developed their own terms to define their relationship with the low light, the damp surfaces, the gray. Indeed, wherever one lives, one develops a way to relate to the climate, weather, and environment as a biological, intellectual, and creative response. I chose to channel my creative energy and a small moment of everyday practice to produce and enhance this relationship.

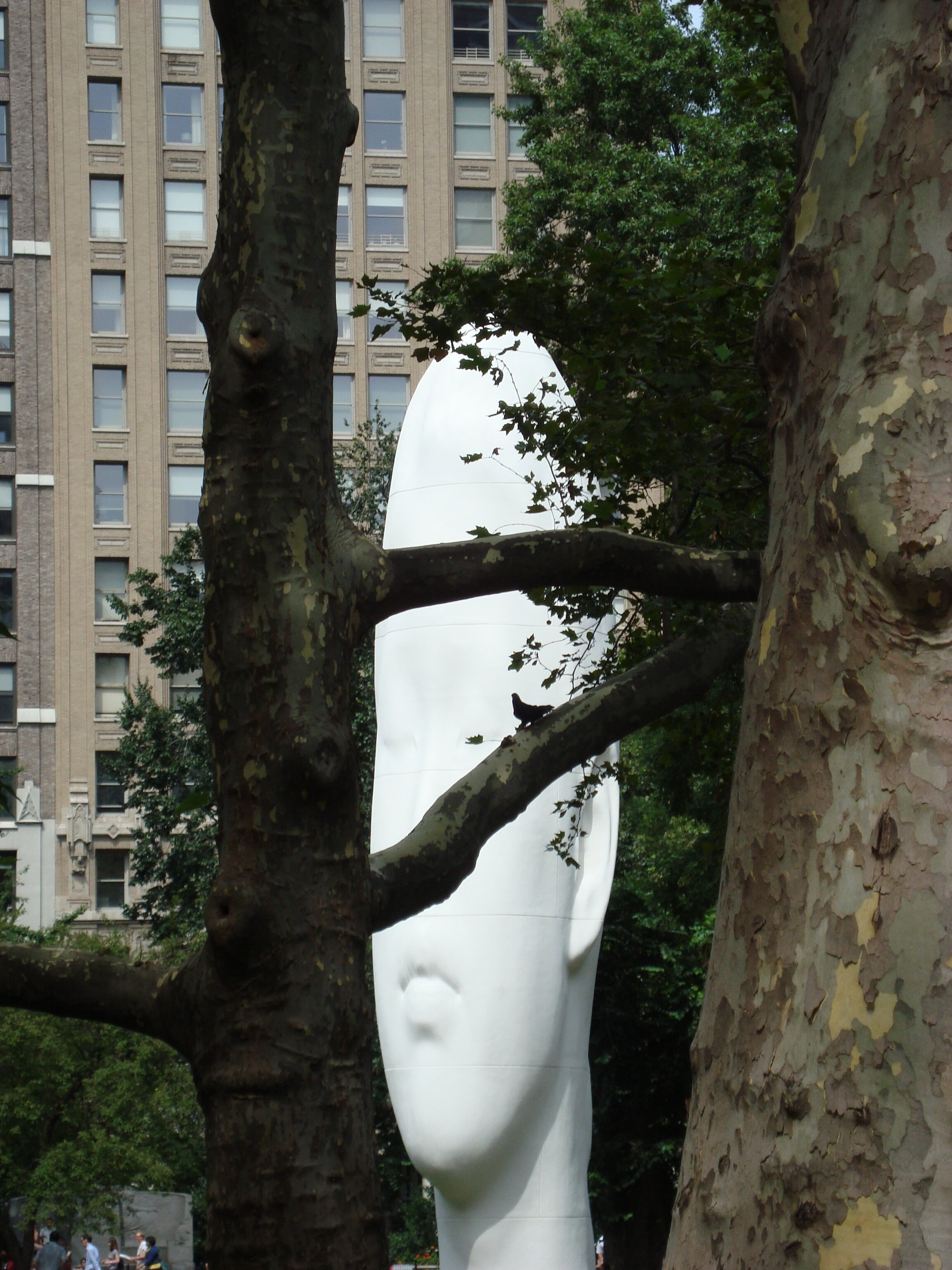

The calendar created a way for me to counter the leveling and monotonous consistency that is Pacific Northwest rain. To establish rain as a collection of individual drops not an even drizzle. To remember that behind the low clouds which seem to emerge impossibly from below the horizon is the sun. To imagine that the base of the trees, hills, and city extending up through the cloud base are extending into a world of infinite imagination and inquiry… Does the hill crest? Does the tree ultimately reach the sun light it seeks? Is the city in the clouds able to extend toward a more creative and just world? My calendar was never meant to be able to fully negate the reality of walking the damp and low light city but as a way to reveal the resident potential. To open me up to creative moments that cut through that low light and dampness to see the possible reflecting off the brilliant surfaces. What I was not expecting was how the calendar began to effect how I engaged not just my environment but my larger perspective on life and creative potential.

These daily moments of pause and gauging the environment around me began to give me perspective within the other life flows that can often overwhelm, become default, or be thought of as fixed. Each pause at the beginning of the day became an acknowledgement of the day ahead. That I was entering a beginning and into a day that was most definitely open. Open to creativity, new avenues and an opportunity to make. As Jean Gardner (Parsons) one of my mentors continues to advocate - “…you make your path, you do not find your path. Always focus your energy on making the path you want and all that your creativity can imagine.”

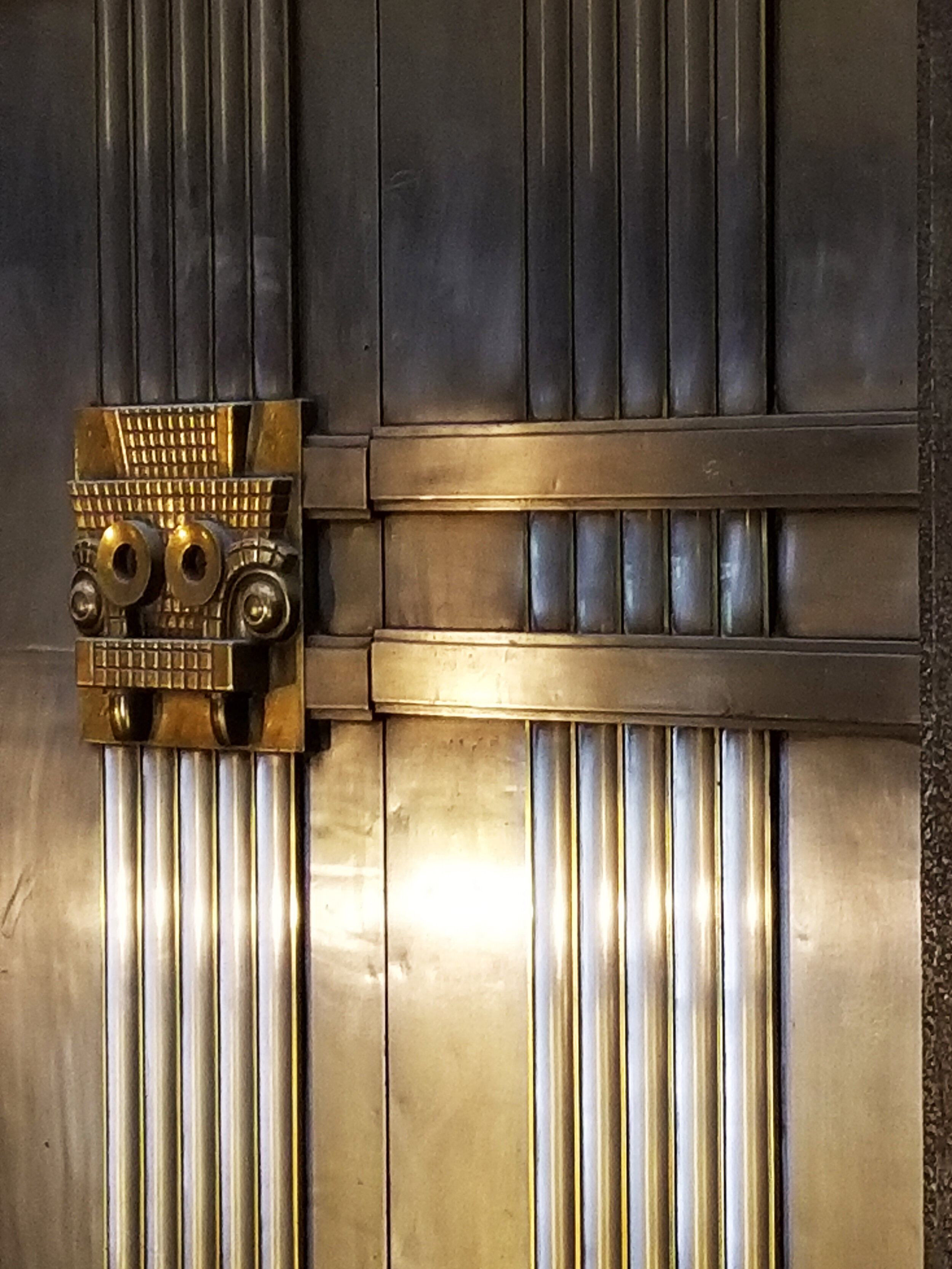

Each daily pause also provides a moment to breathe. The two or three breaths taken while I reconfigure tiles, over time has come to parenthesize all other flows and distractions. It is a small moment that over the past decade I have come to value. The fact that these moments are so small is what makes them so meaningful. Just as the accumulation of small rain drops transforms the city, so this collection of now thousands of breaths has transformed me.

A Rain Day

The rain calendar is now along with me as I make my way in the form of distinct shifts in my body. This is manifest most clearly through a smile that emerges on my face as it begins to rain. I do now ‘smile at the rain’ as Beth Logan and her ever-present painting of Seattle rain asks us to do. I am not sure exactly when the shift occurred but it is now pervasive. Rain begins to fall and I smile. While the daily changes to the installed tiles do entail important breathing, the coming of physical rain drops landing on my face creates a direct shift in my body. A smile reshapes my face. I tend to look up momentarily. This shift in view adjusts my posture and my back becomes more vertical. My weight shifts forward and the next steps I take are from the balls of my feet. It is as if my body is aligning to be ready and be capable to make the most of what is next. The environment around me is changing and my spirit and body are working to align to this shift and become best situated. Finally, I whisper to myself - “a rain day.”

Calibration

This reflection brings forward theories of Evernden, Butler, Lefebvre, Husserl, and others which could be used to calibrate my thinking. However, a comment made by a friend and former colleague Glenn Myles (McGranahan) a couple years back resonates the most during this reflection. “Matthew your calendar is quite Biophilic.” Yes, the calendar is abstract but it does reflect (in Ryan, Browning et. al. phrasing) a deep-seated need to connect with nature. The calendar does engage in patterns that function to provide psychological, physiological, and cognitive benefits. The calendar makes observable to me a pattern of my experience of rain without the intent to separate my experience but to further connect my experience to my environment. This opens up a larger question of how abstraction is engaged to define experience and the environment. A rich question to open… Does abstraction necessarily presuppose a problematic negation of the environment? Can abstract representation be effectively linked to the environment as to not require defaulting to theories that necessitate a need to establish abstract classification, erasure, negation, and on to othering? A few solid questions to continue to approach over the next decade of my rain calendar…

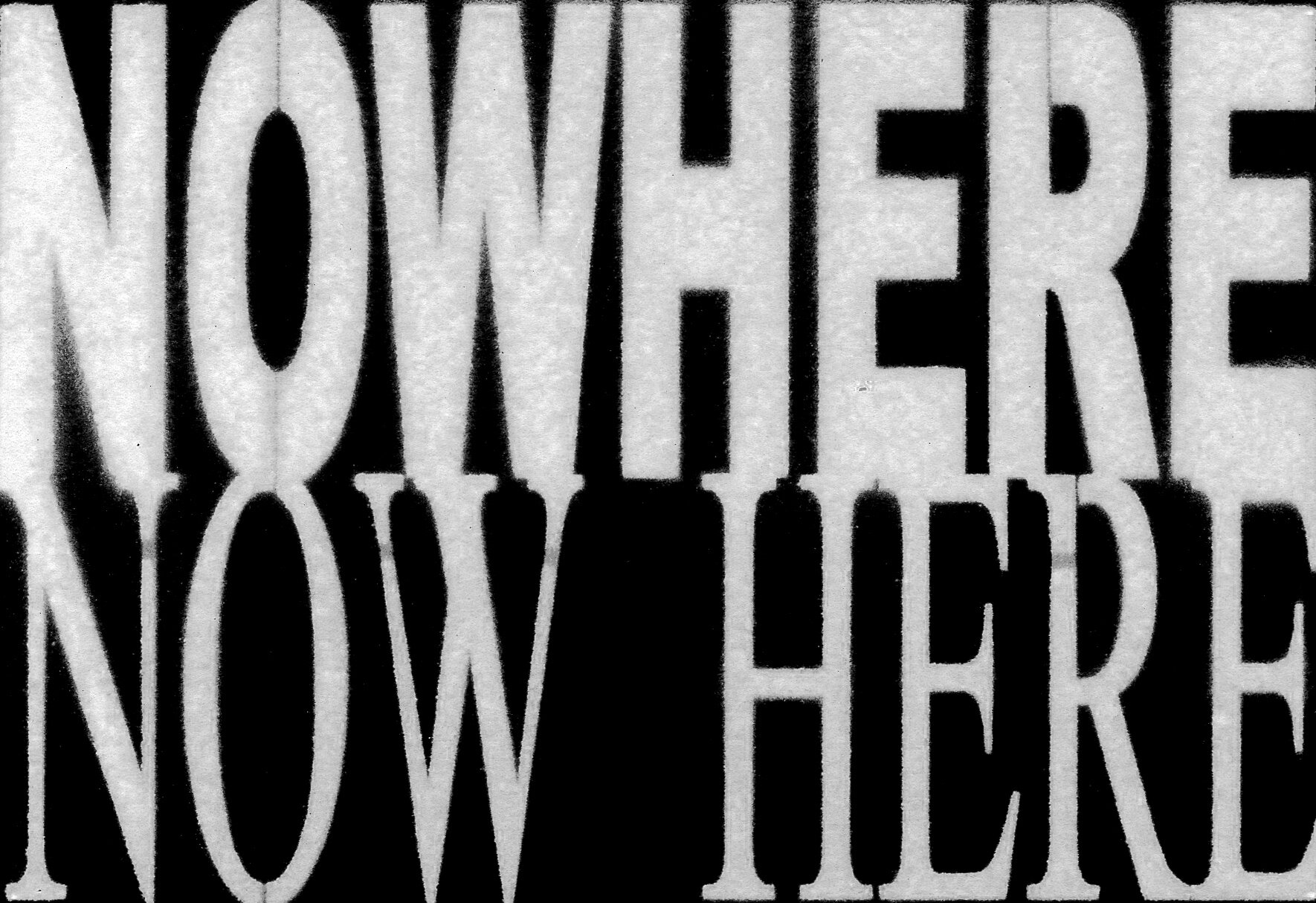

Sun Break

As I think of the rich exploration possible over the next decade that the above questions contain another Pacific Northwest phenomena is occurring - a sun break. A phrase used to describe a small momentary break in the clouds that allows the sun to penetrate through the thick gray blanket pulled over the city. I have always liked this phrasing. While it is technically a break in the clouds the phrasing focuses on what is acting within or is possible from the break - the sunshine. The phrase is turned to describe the positive environmental result not the shift in the condition or constraint. A phrasing that acknowledges, in my thinking, that the sun was always there and always working to warm us and provide light to our day. A small shift is all that is needed to bring the brilliance and warmth into view regardless of how short lived. After all, as the phrase indicates this is a time dependent phenomena and the break will end soon and the rain will return. Until then, the sun break illuminates a kaleidoscope of brilliant light reflecting off of rain soaked surfaces from all directions. A low cool light transformed, for a moment, into an all encompassing brilliant warm light.

Today was a rain day.